Confederate Truths: Documents of the Confederate & Neo-Confederate Tradition from 1787 to the Present.

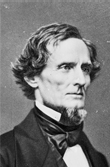

Jefferson Davis's white supremacist and pro-slavery views in his memoirs published in 1881

Jefferson Davis on race and slavery in his memoirs, no lessons learned.

After the Civil War, Jefferson Davis' two volume book, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, was published in 1881. The United Daughters of the Confederacy have always promoted Jefferson Davis as a great thinker, hero and American, and do so to this day, and had these two volumes reprinted in the early 20th century. These are some extracts from it. You can see that he learned nothing from his experiences and was racist and pro-slavery to the end of his life. He died in 1889.

In Vol. 1, pp. 3 Jefferson Davis condemns Abolitionists.

A few zealots in the North afterwards created much agitation by demands for the abolition of slavery within the states by federal intervention, and by their activity and perseverance finally became a recognized party which, holding the balance of power between the two contending organizations in that section, gradually obtained the control of one, and to no small degree corrupted the other.

In Vol. 1, pp. 29, Jefferson Davis feels Abolitionists misuse the word "Liberty" in wanting it for slaves.

Thus, by the activity of the propagandists of abolitionism, and the misuse of the sacred word Liberty, they recruited from the ardent worshipers of that goddess such numbers as gave them in many Northern states the balance of power between the two great political forces that stood arrayed against each other; then and there they came to be courted by both of the great parties, especially by the Whigs, who had become the weaker party of the two. Fanaticism, to which is usually accorded sincerity as an extenuation of its mischievous tenets, affords the best excuse to be offered for the original abolitionists, but that cannot be conceded to the political associates who joined them for the purpose of acquiring power; with them it was but hypocritical cant, intended to deceive.

In Vol. 1 pp. 66, Davis on slavery.

As a mere historical fact, we have seen that African servitude among us ?confessedly the mildest and most humane of all institutions to which the name "slavery" has ever been applied?existed in all the original states, and that it was recognized and protected in the fourth article of the Constitution.

In Vol. 1, pp. 70-71 Jefferson Davis praises the notorious Chief Justice Taney and his infamous Dred Scott decision and condemns those who condemned the Dred Scott decision. .

In 1854 a case (the well-known Dred Scott case) came before the Supreme Court of the United States, involving the whole question of the status of the African race and the rights of citizens of the Southern states to migrate to the territories, temporarily or permanently, with their slave property, on a footing of equality with the citizens of other states with their property of any sort. This question, as we have seen, had already been the subject of long and energetic discussion, without any satisfactory conclusion. All parties, however, had united in declaring that a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States?the highest judicial tribunal in the land?would be accepted as final. After long and patient consideration of the case, in 1857, the decision of the Court was pronounced in an elaborate and exhaustive opinion, delivered by Chief Justice Taney?a man eminent as a lawyer, great as a statesman, and stainless in his moral reputation?seven of the nine judges who composed the Court concurring in it. The salient points established by this decision were:

- That persons of the African race were not, and could not be, acknowledged as "part of the people," or citizens, under the Constitution of theUnited States

- That Congress had no right to exclude citizens of the South from taking their negro servants; as any other property, into any part of the common territory, and that they were entitled to claim its protection therein;

- Finally, as a consequence of the principle just above stated, that the Missouri Compromise of 1820, insofar as it prohibited the existence of African servitude north of a designated line, was unconstitutional and void. (It will be remembered that it had already been declared "inoperative and void" by the Kansas-Nebraska bill of 1854.)

Instead of accepting the decision of this then august tribunal—the ultimate authority in the interpretation of constitutional questions—as conclusive of a controversy that had so long disturbed the peace and was threatening the perpetuity of the Union, it was flouted, denounced, and utterly disregarded by the Northern agitators, and served only to stimulate the intensity of their sectional hostility.

In Vol. 1 pp. 262-263, Jefferson Davis again defends slavery.

A passing remark may here be appropriate as to the answer thus afforded to the clamor about the "horrors of slavery."

Had these Africans been a cruelly oppressed people, relentlessly struggling to be freed from their bonds, would their masters have dared to leave them, as was done, and would they have remained as they did, continuing their usual duties, or could the proclamation of emancipation have been put on the plea of a military necessity, if the fact had been that the negroes were forced to serve, and desired only an opportunity to rise against their masters?

In Vol. 1 pp. 458, Jefferson Davis quotes a speech as the U.S. Senator for Mississippi in the Senate, Feb. 13 and 14, 1850. In 1881, still endorses the assertion of this speech. I quote a part of it.

... They see that the slaves in their present condition in the South are comfortable and happy; they see them advancing in intelligence; they see the kindest relations existing between them and their masters; they see them provided for in age and sickness, in infancy and in disability; they see them in useful employment, restrained from the vicious indulgences to which their inferior nature inclines them; they see our penitentiaries never filled, and our poor-houses usually empty. let them turn to the other hand, and they see the same race in a state of freedom in the North; but instead of the comfort and kindness they receive at the South, instead of being happy and useful, they are, with few exceptions, miserable, degraded, filling the penitentiaries and poor-houses, objects of scorn, excluded in some places from the schools, and deprived of many other privileges and benefits which attach to the white men among whom they live. And yet, they insist that elsewhere an institution which has proved beneficial to this race shall be abolished, that it may be substituted by a state of things which is fraught with so many evils to the race which they claim to be the object of the solicitude! Do they find in the history of St. Domingo, and in the present condition of Jamaica, under the recent experiments which have been made upon the institution of slavery in the liberation of the blacks, before God, in his wisdom designed it should be done?do they there find anything to stimulate them to further exertions in the cause of abolition? Or should they not find there satisfactory evidence that their past course was founded in error?

In Vol. 2 pp. 161-162, in anger at Abraham Lincoln's joy at the enlistment of African Americans into the U.S. Army.

Let the reader pause for a moment and look calmly at the facts presented in this statement. The forefathers of these negro soldiers were gathered from the torrid plains and malarial swamps of inhospitable Africa. Generally they were born the slaves of barbarian masters, untaught in all the useful arts and occupations, reared in heathen darkness, they were transferred to shores enlightened by the rays of Christianity. There, put to servitude, they were trained in the gentle arts of peace and order and civilization; they increased from a few unprofitable savages to millions of efficient Christian laborers. Their servile instincts rendered them contented with their lot, and their patient toil blessed the land of their abode with unmeasured riches. Their strong local and personal attachment secured faithful service to those to whom their service or labor was due. A strong mutual affection was the natural result of this lifelong relation, a feeling best if not only understood by those who have grown from childhood under its influence. Never was there happier dependence of labor and capitol on each other. The tempter came, like the serpent in Eden, and decoyed them with the magic word "freedom." Too many were allured by the uncomprehended and unfilled promises, until the highways of the these wanderers were marked by corpses of infants and the aged. He put arms in their hands, and trained their humble but emotional natures to deeds of violence and bloodshed, and sent them out to devastate their benefactors. …

In Vol. 2 pp. 600, in his condemnation of the Emancipation Proclamation, Jefferson Davis in his book reprints his proclamation of January 1863.:

A proclamation, dated on January 1, 1863, signed and issued by the President of the United States, orders and declares all slaves within ten of the States of the Confederacy to be free, except as are found in certain districts now occupied in part by the armed forces of the enemy. We may well leave it to the instinct of that common humanity, which a beneficent Creator has implanted in the breasts of our fellow-men of all countries, to pass judgment on a measure by which several millions of human beings of an inferior race?peaceful, contented laborers in their sphere?are doomed to extermination, while at the same time they are encouraged to a general assassination of their masters by the insidious recommendation "to abstain from violence, unless in necessary self-defense."

In Vol. 2, pp. 628, Jefferson Davis praises a Virginia judge who closes his court rather than allow African-Americans serve as jurors. It also shows how Davis' racism is cloaked in the rhetoric of a high minded defense of the law. This is an event in 1867. Jefferson Davis has a lengthy foot note comparing this racist judge to the heroes of the American Revolution.

The question of the qualification of jurors now became important. General Canby issued an order on September 13th, which required the jurors to be drawn from the "qualified voters," which included the newly emancipated slaves. The judges met, and sent a respectful request to the general to change the order to conform to the law of the state. By the jury law, as it then stood, no person was qualified to serve as a juror unless he was a free white man, twenty-one years of age. The judges were sworn to enforce the law and the constitution of the state. No notice was taken of the application. At the next court in Edgefield, Judge Aldrich, charging the grand jury, brought to their notice the order, the law and the constitution, and the oath of office, and then declared "he could not and would not obey the order." On going to open court a few days after, the adjutant of the post delivered to him a military order suspending him from office. He proceeded and opened the court, read the order and stated the circumstances, and, laying aside his gown, directed the sheriff, "to let the court stand adjourned while justice is stifled."1

The lead in of the footnote is as follows:

This incident in the conduct of the judge recalls a like exhibition of judicial purity and independence which occurred in the colonial history of South Carolina, and which I present by extracts from the charge of Judge William Henry Drayton, delivered November, 1774. …